I have an uncontrollable, wallet-draining, body-wearying museum addiction. I skim magazines for openings, read and take notes on exhibit reviews, and those guidebooks, which never quite capture the essence of a city, become checklists, because more museums than I could see in a year are listed in one place. Each rumour of a new museum gleaned from the internet or by word of mouth — the Museum of Things, for instance, which I have yet to see listed in a travel guide but is well worth a visit — has me working out tram, train, and bus connections across the city to wherever I must go to indulge my obsession. To me, the Lange Nacht der Museen, the bi-annual museum crawl through Berlin, when the museums are open until two a.m., was irresistible.

Vagabondish is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission. Read our disclosure.

Berlin’s Lange Nacht der Museen

When we left the house it was damp and warm, Berlin ghostly through a veil of fog. We were bundled in more layers than seemed necessary — long underwear, extra sweaters, hats and gloves — because the soft warmth of dusk never lingers and a damp cold can transform a pleasant night out into bone-aching misery. By the time we emerged from the subway at Potsdamer Platz, the fog had become heavy rain, tossed around by sideways winds; we were glad of the extra clothes, though the umbrella I had grabbed on the way out the door was superfluous even as a wind-break. Germans generally don’t talk about the weather, but they do when it’s like this. “It’s shit,” they say, “Just shit.” We didn’t disagree.

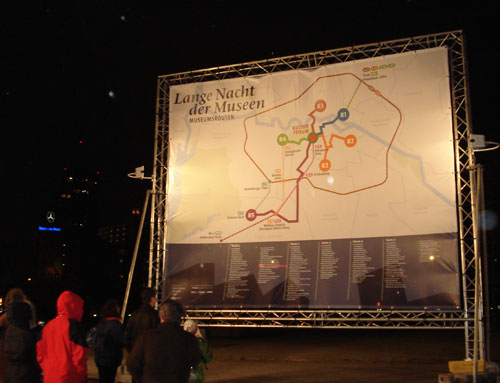

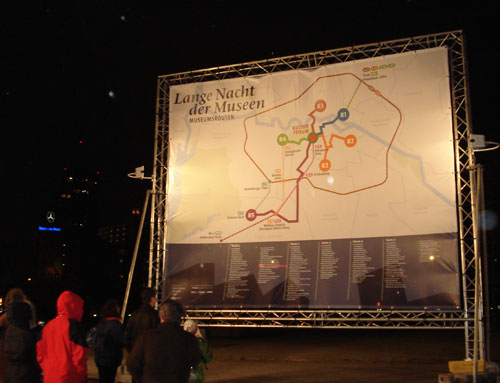

We had spent the afternoon flipping through the brochure, highlighting places we could grab a bite to eat, marking lectures and presentations that sounded interesting, and drafting ambitious itineraries and rejecting them when something more exciting turned up. The theme of Berlin’s 22nd Long Night of Museums was “Zeit”, time, and the trouble was we didn’t have enough of it.

Video Installation at the Kulturforum

Our evening began at the Kulturforum near Potsdamer Platz, from which the five routes to the various museums spread out like spokes. Out front, visitors could participate in a video installation on the theme “Zeit”, wandering through machine-made fog and over engaging with images on screens above their heads. We might have lingered there, playing with the ghostly words, which trembled as the wind pushed at the poles that held the machines from which they were beamed onto the pavement, but were caught up by a gust and flung toward the bus stop. Matthew, who has a thing for organs, wanted to see the organ tour at the Berliner Dom, so we started on Route 1, the route to the Museum Island, where so many of Berlin’s top museums are located.

The bus was crowded, more crowded than the city buses are at rush hour. It smelled like damp wool, and the driver stopped only to let passengers off; there wasn’t room to let any more on. Public transit might have got us there more comfortably — the tickets for the event included a transit ticket — but the museum shuttle service, doorstep-to-doorstep, was ideal in the rain. I’ll share space with someone’s suitcase-sized purse if it means keeping my commute as short as possible.

The Berliner Dom is an eight-sided building in the Italian Renaissance style. Six sides, the guide told us, represent the days God spent creating the Heavens and the Earth, the seventh, the day he rested, and the eighth, eternity. Models of possible designs for the cathedral are displayed in the museum-space upstairs. In that same corner of the cathedral stairs lead up to a viewing platform on the cathedral dome which is said to offer a glorious view of Berlin-Mitte. I wouldn’t know. The winds were so strong that the staff was worried about visitors blowing off. Two security guards were posted at the door to turn people away.

In its day, the organ in the Berliner Dom was the largest in Europe. The organist showed us how it made sounds so low they can only be felt, and how it could imitate the sound of a clarinet. When he played the Vox Humana without accompaniment, I was struck by how small and weak the imitation of the human voice sounds. It was an impressive instrument, grand and imposing, and in my opinion (not always being fond of Renaissance architecture), the most interesting part of the cathedral. Although the cathedral dome was, we were told, opened up by the kind Americans, the organ survived the war but fell victim to looting in the desperate years after, as pipes were taken out and the metal used to create more practical things. There would be an organ concert later on, but I was determined to see more of Berlin’s museums, and opted not to stay.

If the Mitte Museum am Festungsgraben (German language) attracted us more than some of the flashier museums, it was for the “Sensing the Street” exhibition, put on by students at two of Berlin’s universities. The exhibit, a “street ethnography” of Ackerstraße, an ordinary street in the Wedding district of Berlin, promised sound and video installations, smell-boxes and sensation points, allowing visitors to “feel” the street. I liked the premise. Unfortunately, the exhibit was sterile and static, offering little reflection on the area and failing to represent the life and history that has quietly written itself into the stones of the sidewalks and the walls of the houses that line the street, with the flow of time. The smell-box (there was only one) smelled like a new pressed-fiber box from IKEA; it didn’t contain a scratch-n-sniff Berlin, but recordings of people describing what they smelled on the street. Where’s the fun in that? Matthew was outraged.

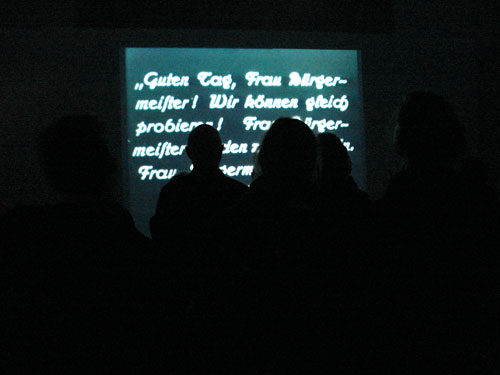

At the Karl Valentin Exhibit

“Sensing the Street” was a bust, but the museums were open for another four hours, so we set out for the exhibit on Karl Valentin at the Martin Gropius Bau, a building which is as famous for its architecture as for the exhibits they put on there. We were weary and cold, and Valentin, the clown who became a media pioneer, seemed the perfect remedy. By this time, the crowds were beginning to thin out, but the small viewing rooms where two of his films (a silent one, and a later one with sound) were playing, were full, and at first, I had to crouch on the floor at the back of the room. When we settled down to watch, we expected a short film, or a series of shorts, but found ourselves absorbed in Der Sonderling, laughing, unwilling to leave. Anyone who would suggest that Germans have no sense of humour should watch one of Valentin’s movies, preferably with an audience of Germans; the physical comedy is enchanting, and it’s impossible not to laugh. If you’re interested, the exhibit runs until the 21st of April.

On the bus, we realized that we were too late to catch any of the lectures we had highlighted at the next destination on our list, the Botanical Museum. Though we still had time to visit the Deutsches Blinden-Museum Berlin, the museum of the blind, there was one final museum we didn’t want to miss: the Museum der Unerhörten Dinge, that is, the Museum of Unheard-of Things. We were realizing something that we already knew — museums take time — and rather than miss this counterpoint to the Museum of Things, which we had visited just two weeks before, we stayed on the bus until it looped back toward the Kulturforum and got off a block from the museum.

Museum of Unheard-of Things

At 1 a.m., the Museum of Unheard-of Things was still so packed, it was impossible to move. Not surprising, considering the size of the place. The Picture of Dorian Grey, petrified ice, pieces from Walter Benjamin’s typewriter, and a twenty-four hour candle, among other things, were meticulously displayed, accompanied by laminated explanation cards which told fantastic stories about the objects, or, if an object was not completely impossible, how it had been acquired. The Museum depot was open, so that visitors could examine unheard-of things yet to be catalogued, and the curator was glad to answer anyone’s questions. He also had a book, a sort of catalogue of the exhibit, available for sale. It was a perfect ending to the evening, a snappy comment on museums, on cataloguing, and on how we assign meaning to objects, but most of all, it was a whole lot of fun.

I’ll be sleeping off the museum-hangover for days.