There are few places in Europe that encompass almost every cultural category or way of life as well as a certain little marketplace hidden in an Industrial Revolution-era canal-side nook. Here you can feel the pulse of the twenty-first century global economy in action, and the excitement of a thousand different faces speaking a hundred unique languages in cobbled alleyways.

Vagabondish is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission. Read our disclosure.

It’s known to its 150,000 weekly visitors, but far enough off the tourist map to retain its authenticity. It has no historic sights or costumed tour guides, just a smorgasbord of sights, sounds and smells as exotic as any you’ll find””and it’s located just a few short tube stops away from Big Ben. After the tourist attractions are stale, come here to experience the real London; “grotty”, wild, authentic, amusing and sometimes shocking. Come to Camden.

Four People, Camden, London © Colin Grey

This place, the majority of which is located between Camden Town Station and Chalk Farm Road, is so diverse that a quick walk-through can shock the system of the unprepared. The entrance to what seems like a small outdoor market near beckons, and soon you’re bobbling down cobbled alleys teeming with sounds, colors and music, all blending into one living Kaleidoscope of commerce and temptation. And that’s just the first ten feet.

Like so many of the great European cities, the quaint mazes of Camden have been saved and recycled by a new generation of capitalists. The new look of the place highlights the demographic changes that have transformed London in the span of a half century. The subjects of the British Empire have come home to build a better life. The Victorian-era commercial district near the Lock over Regents canal is now bursting with shop owners of every imaginable ethnic background, many from nations still in the painful early stages of developing a democracy and free market economy. These vendors are Londoners by choice, not by birth, and they understand market economics and the entrepreneurial spirit as well as any western tycoon.

Your first experience with this place might be a bit shocking. You don’t expect to be enveloped in a labyrinth of tight alleyways and sensory overload from every corner of the known universe. I’d arrived in London after backpacking and hitching rides through the UK for three weeks. After a very long day of sightseeing I began to feel a little burnt-out on the familiar, relentlessly commercialized touristy-ness of the major downtown sights. I had a longing to find the real beating heart of the city, the guts of the place. I bought an all-day tube ticket and rode the underground without any specific agenda other than to see the places that the tourists miss. As any seasoned traveler knows, those places are always where the real stuff is hidden.

Tube Graffiti in Camden, London © bixentro

I hopped off the Northern line at the Camden stop where a busy street of bustling shoppers greeted me as I left the station. After a brief walk, I turned left down a pleasant pedestrian path to escape the throngs. Upon crossing a little bridge over a gently burbling man-made canal, a holdover from the industrial revolution, I entered a charmingly “grotty” old warehousing district that was a hive of business activity during the Empire’s glory days. Turns out it still is.

As I rambled down the narrow alleys, I was dazzled: on my left, a mysterious-looking Egyptian antiques dealer was waiting in his dark little shop full of musty relics. Across from him was the Turkish rug store where the owner stood outside, hollering something at passersby while pointing excitedly to an ornate rug that wouldn’t have been out of place in a medieval Ottoman ruler’s bedroom.

The stall rubbed shoulders with a punk-rock apparel shop. A clerk with green hair, knee-high combat boots and more than a few lip rings blasted furious music; I walked by and immediately passed through a plume of thick, greenish smoke emanating from a cluttered little hole in the stone wall. The gentle strains of Bob Marley began to fill my ears as I peered though the grey haze and saw a vast array of little pink and purple gadgets sold by a Jamaican with long dreadlocks. Most tourists would assume it was a cute little vase shop. But some of us know better.

Anarchy at Camden Market, London © FaceMePLS

Passing these up, I headed for a larger space to clear my mind. I picked what seemed to be a good location for this activity””what looked like an unused nook of the old Victorian complex””and immediately became lost in a maze of moldy brick corridors; the sudden cool clamminess of the stones giving off a distinctly Jack the Ripper-sh atmosphere.

After another turn I find myself enveloped in a futuristic clothes shop of thumping club music and pink outfits that were reminiscent of the mid-sixties Carnaby Street getups. Lights were flashing onto silver foil which covered the walls and the throbbing music was pumped down from hidden speakers. It all made me feel a little disoriented. In some countries this is called torture. In Camden, it’s called retail.

Though the funhouse atmosphere quickly became almost nausea-inducing, the neo-Goth clerks didn’t seem to mind. They seemed to have spent some time at the Bob Marley Pink Vase Emporium just before I arrived. I finally made it to the exit and found myself back in the midst of the bead shops and Vietnamese food vendors, happy to see the outside again.

Passing by a novelty t-shirt stall, I struck up a conversation with a guy who was obviously not a native Englishman. I wanted to know his story, thinking it might be representative of this wild community of entrepreneurs. I didn’t want this visit to pass me by without talking to someone who was here for the parade every day, trying to eke out a living amongst the mayhem. He was a friendly young Sri Lankan guy in his early twenties with an indecipherable name.

I didn’t want this visit to pass by without talking to someone who was here for the parade every day, eking out a living amongst the mayhem.

I asked what had led him from Sri Lanka to this place. “Opportunity,” he said with a broad, toothy grin, the whiteness of his teeth contrasting with his dark complexion. He told me that the chance to come to the capitol of all capitols and escape the crushing poverty of his homeland was a dream he would not be denied. He left his parents, village and everything he knew to come here, and he is in good company. “Here, I can be anything I want, run a business, it is good,” he said.

Pockets of London, including Camden, contain some of the densest and most varied immigrant neighborhoods in the world; a crash-course in extreme multiculturalism, and sometimes poverty.

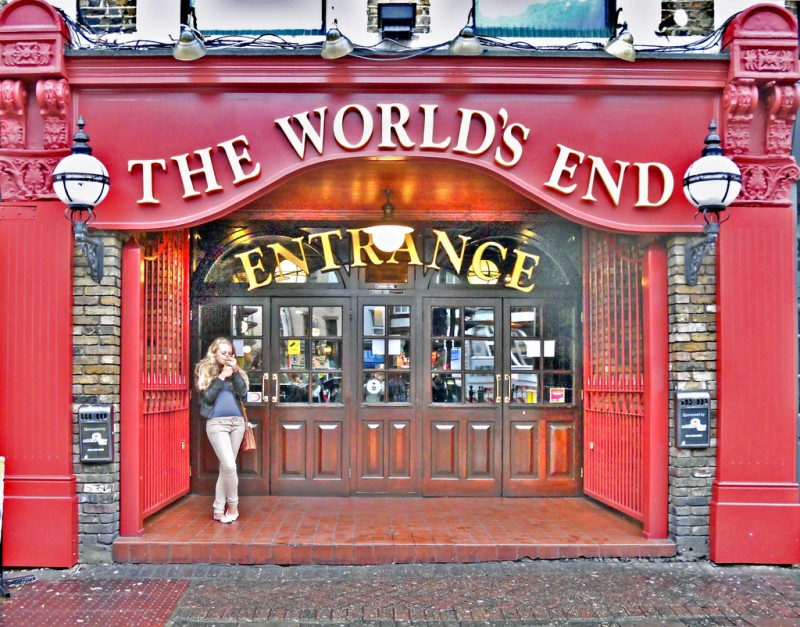

World's End Pub in Camden, London © Duncan Harris

“Here I am,” he said with pride, “selling things from my home country among every other nationality there is.” He then began fiddling with his iPhone. His parents probably didn’t have electricity. Then he smiled and leaned toward me as if preparing to expose a great secret: “Many tourists pass right by, but those who come will find what they are looking for. There is something for everyone here, my friend. Just come and find it.” I was unsure whether he was referring to the market, or the broader meaning of London’s hidden nooks and crannies. He could have meant both.

Camden has so much to see, do, hear, smell and eat. It is a vibrant, thriving reminder that our diverse world is getting smaller by the day. Aside from the good shopping and delicious, cheap lunches from anywhere on the planet, a visitor will take home a much richer memory than anyone on the big red tour buses can buy. No need to buy a ticket or book ahead; it’s free, so just show up.

Want to get the pulse of the Capitol City? After Big Ben and St. Paul’s have given you all they can and you’re ready for a tasty, shocking, cobble-stoned carnival of everything modern-day London has to offer, come here. Come to Camden.