Provocative, lavish, bawdy, and elegant, Shanghai is the stuff of legends. It has a reputation that lures travelers of every ilk, that whispers diverse, contradictory promises of the treasures concealed in its secret alleys: the richest, most delicate Dongpo rou of your life; one last opium sanctum languishing in the shadows; a Confucian temple dwarfed by the newest, tallest skyscraper in the world. If you looked in the right places, what would you find?

Vagabondish is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission. Read our disclosure.

The Shanghai that I encountered is, of course, a city of many faces””some bewitching, others harrowing.

And yet, when I close my eyes I am still rapt by its myth. When I remember the night sky above the Huangpu River on the first new moon of the year, Shanghai seems to glitter with a special brilliance.

—

A compilation of hundreds of years of annual celebrations, the Chinese New Year is a festival among festivals. Heralding the first day of the first lunar month, which, measured by the Gregorian calendar, generally falls in late January or February, the holiday accedes to another turn of the zodiac, as the year of the monkey or rooster is ushered out and the year of the dog or pig is heartily inaugurated. Plenty of scurrying and bustling occurs as people make preparations for a new start, sloughing off the umbra of a passing year. It is amid such celebration, on a chilly day in late winter, that I make my way into Shanghai.

There’s something disorienting and wonderful about entering a city for the first time by subway. The underground tunnels hardly reveal anything about the streets above, about the thousands of daily-life tableaus staged only meters away yet never glimpsed. At Henan Zhong Road station, the subway doors slip apart, spilling passengers into the cool, musty recesses of the station. Crouching musicians spin erhu melodies through the dirty tiled hallways and eye passersby for spare change. As the escalators rise toward the sunny exit, their songs recede in the dim tunnels. Their supplications become inaudible.

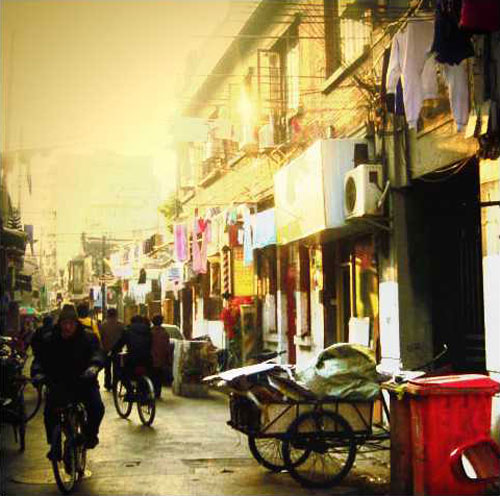

Workday, Shanghai © Aya Padrón

Aboveground, the city blazes with crimson decorations. Here, at the confluence of East and West, calligraphy shops brimming with brushes and inks disappear behind rows of oblate red lanterns that cling to art-deco architecture evocative of spunky flappers and gypsy jazz. On the street, holiday revelers stroll determinedly, cramming themselves into the narrow spaces between strangers as they navigate Nanjing Lu, one of China’s best shopping streets. Today, it sputters with activity. From a cluster of food stalls near the metro, three girls emerge with steaming meals, dropping their chopsticks into plastic bowls of stinky tofu, the odor sour as they pass. Within minutes, they are lost among the crowds. Further on down the street, a boy pauses to peel tea eggs beneath the neon towers of Shanghai’s colossal department stores, while in the sidewalks skirting Nanjing Lu and Xizang Lu, a young girl trails foreigners with her palm extended. Across the street, a woman shifts her baby onto her hip and pursues a white couple until at last they drop some kuai qian into her hand.

In the January air, a whiff of charcoal is detectable, then other scents: grilled meat, cigarettes, steamed buns. An old woman hawks glossy candied crabapples skewered on wooden sticks. Some local men murmur in English as they pass, “handbags ”¦ watches … DVDs…” Families carry youngsters swaddled in colorful snowsuits. Menus on the windows of restaurants proclaim in English and Chinese that a great variety of dishes are prepared within: “Dongjian salt-baked chicken,” “cold big clab,” “tea-flaroured pigeon,” “roast duck with plum’s paste,” “barbecued pork in honey syrup,” “oxtail parfait.” And through the smog, the spires and steeples of futuristic skyscrapers crown the cityscape in all directions.

When the sun starts to set in the cloth and antique markets of the Old Town, the streets glow golden and commuters on bicycles set out for home, perhaps to New Year’s Eve dinners with their families. They go by the hundreds, riding two, three, four abreast, veering and shouting and narrowly avoiding collisions. On a quieter side street, someone carrying a big, fake tiger skin patrols the sidewalk scanning for tourists. Up and down the alley, vendors sit on metal folding chairs and stare silently at their crates and crates of oranges, Pepsis, and silver fish, waiting for a sale. As the last of the sunlight fades, caged birds at a market twerp, ruffle their feathers, and hunch lower on their roosts. Above them, laundry hung from roofs or trees quietly flutters, and telephone wires trace a chaotic route between and through the aging buildings.

At dusk, the fireworks begin. And they never end. It is unimaginably constant. Every second, some corner of the city emits a booming sound that echoes off buildings and contributes to a general tremor-like rumbling in the streets. Crowds flow along the riverside boulevards and listen to the thunder, watching as beads of glassy colors soar skyward above the baroque and neoclassical architecture of the Bund.

Lunar New Year Celebration, Shanghai © Aya Padrón

Looking straight up into the stars from the river’s edge, all of the skyscrapers sunk into the periphery, it could be a night sky from an era long past. What emperors of fallen dynasties gazed into fireworks displays like these? The tradition of New Year’s Eve pyrotechnics is entwined in myth. Old stories testify that they were employed in legendary battles against the monster Nian, which materialized from its hidden lair around the beginning of the lunar month to besiege villagers. Combatants used firecrackers to drive off the beast, for the monster, though a fearsome foe, could be frightened away by loud noises.

From a dimly lit jazz bar on the fifty-third floor of the Jin Mao Tower, the firecrackers below look like brilliant, instantaneous flowers before their indigo or amaranth sparks fizzle in the dark river water. The Oriental Pearl Tower presides above, casts a formidable reflection across the Huangpu, and pulses decisively. Just as a waiter arrives to deliver a cherry cocktail, the female vocalist murmurs that it’s midnight and wishes everyone a happy new year. I turn toward the window. A thick, flat cloud of smog and haze forms a low ceiling above Shanghai, projecting the light from local explosions across the entire city. All night long, it continues — fireworks shimmering in all quadrants of the sky.