People usually hope an earthquake or a tornado doesn’t get in the way of their vacation. But a disaster tourist would be more likely to put themselves in the way of such a natural disaster. It’s really true that there are people who hear of a huge landslide or a tsunami and immediately start looking for the cheapest ticket into the disaster zone. Less extreme are the travelers keen to see the effects of natural disasters in places they visit. What’s the motivation behind disaster tourism, and are you helping or hindering?

Vagabondish is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission. Read our disclosure.

Before I go on, let’s get some definitions straight. Some people would say disaster tourism is a form of grief tourism, or even vice versa, but let’s simplify it by leaving grief tourists at sites where tragic, man-made events have occurred, and let disaster tourists be the ones headed for zones left floundering by natural disasters. Sometimes, of course, the motivations here overlap, but the destinations are usually different.

The Asian Tsunami

I remember the day the Asian tsunami hit during the Christmas vacation of 2004. I was about as far away as one could get, nursing a bad cold in a heated hotel room in Finnish Lapland, glued to the television instead of braving the twenty below temperatures outside. The images I saw that day seemed immeasurably far away, although a few friends who were holidaying in those regions did cross my mind.

Looking back, I’m wondering if I would have been tempted to get involved were I able. For example, if I’d been living in Australia or Japan again, with Thailand just a short, cheap flight away — an even cheaper flight than usual, probably, under the circumstances. I think, for me, the answer is no. That’s both because I’m selfish — I wouldn’t want to put myself in danger — and concerned that it wouldn’t help — what could I really do to help these people, and why would I want to see their devastation?

Ruin of the 2004 Asian Tsunami © notsogoodphotography

A USA Today report at the time juggled both sides of the issue. Like me, they weren’t keen on the idea of tourists arriving to gawk at the destruction — to photograph the buildings that were washed away, or to see the temporary accommodation provided for thousands of people now homeless after the tsunami. But they were also practical enough to point out that a lack of tourists meant a big gap in income for many of these people, and that if tourists stayed away for too long, the economic effect would be nearly as devastating as the tsunami.

Yet the viewpoint from an Indian report is one-sided: tourists who come and take photographs of the tsunami damage do not belong there. On top of that, there is the problem that once rebuilding starts to take place, the tourists and the media lose interest and any help they had been offering seems to slip away.

A number of people headed into tsunami-affected zones in the year or so following the disaster to work with aid agencies and NGOs who were helping to rebuild. Friends of mine chose volunteer vacations in India and Thailand to do just that. Are they disaster tourists? Technically speaking, yes, but I think if they’ve chosen to work with an established aid organization and have skills that can be put to good use there, the stigma of disaster tourism is surely extinguished.

Taking a Post-Katrina Tour

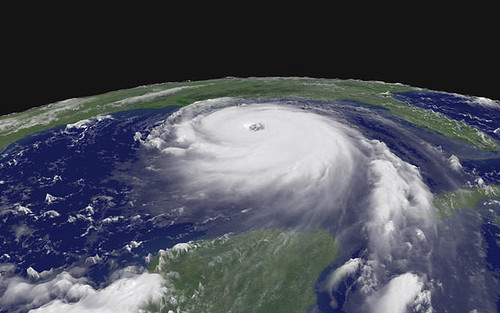

Hurricane Katrina Satellite Image © GISuser.com

The year after the Asian tsunami hit, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, as well as doing a hefty lot of damage nearby. Within a month, bus tours to show visitors the most badly-damaged parts of the city were up and running. Operator Tours by Isabelle, even more than two years after the disaster, advertises the Post-Katrina tour as its feature trip, giving visitors a taste of how things looked directly afterwards. I can’t help thinking that such a tour company won’t be happy when everything’s repaired, because that makes their tour a whole lot less exciting. But this company has obviously encountered some opposition to its Katrina tours, because the description for the New Orleans City Tour comes with a pretty clear disclaimer:

This tour is the City tour as it was done before Katrina. There will be some unavoidable sites of devastation, but they are minimal. This is NOT the Post Katrina City tour.

What do the locals think about tours that highlight the destruction of Katrina? Some are clearly in favor, and believe that if more people see the damage, it’s more likely that such a disaster will be better handled in the future. But others — even tour operators like Isabelle — are unhappy that tourists don’t want to visit New Orleans to see the original reasons it was a popular destination.

So would I take a Katrina Tour if I was visiting New Orleans in the near future? I’d like to sound all high and mighty and so no, of course not. Just by staying in the city and visiting other attractions — hanging around for the Mardi Gras parade, for example — I’d been doing my bit economically by bringing money into the region. The time for urgent or emergency aid has passed, so my presence wouldn’t bring anything particularly valuable. But I have to admit I’d be tempted to take a look.

Is It All About the Timing?

Personally, I think a lot of it comes down to timing. Let me give the example of the Kobe earthquake which hit Japan in 1995. Pretty much all the infrastructure, including water, electricity, gas, roads and trains, were severely affected. Any tourists who had walked into Kobe in late January, 1995, would not have been helping at all.

Kobe Earthquake Memorial © tom jervis

Fast-forward about five years, and Kobe was rebuilt as a beautifully modern city, substantially more earthquake-proof. I visited it many times while living in Osaka in 2001, and I often took visitors to a small section near the harbor which had been left unrepaired as a memorial and reminder of the earthquake’s devastation. The pile of rubble and the crooked lamp post never failed to have an impact on me. The authorities also opened an interesting museum which showed videos of the earthquake and the aftermath, along with many exhibits educating people about what to do in the event of an earthquake. I don’t think anybody who came with me considered themselves a disaster tourist, but perhaps they were.

Here’s what I think: in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster, the only people who should be on an inward-bound plane are those who are experts in helping with disaster recovery, or who are part of a delegation from an aid agency led by such experts. Those with cameras around their necks need not apply.

In the years afterward, it gets a little trickier. See sites of devastation to understand a little better what the locals went through. Get educated about the issues. But don’t go gawking at other people’s misfortunes and pretend that you’re helping their economy, when you’re really only helping yourself. It’s human nature, in a sense, to curiously enjoy seeing suffering, but check yourself and make sure you’re doing the right thing. I’m going to be checking myself any time I’m traveling near disaster zones in the coming years.